Lincoln’s Way

Abraham Lincoln’s political philosophy consisted of only a few ideas, and he believed that America itself was based on these ideas. He said in 1861 that he “never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.” In the same speech, he said that the “great principle or idea” in the Declaration was giving “liberty” to Americans and “hope to the world” that in due time “all should have an equal chance.” At Gettysburg in 1863, he says the same thing: America was “conceived in liberty” and “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Lincoln spoke of democracy like Tocqueville did, and like Walt Whitman did, as both the nation’s form of government and its special reason for existing. He believed that U.S. democracy was “the last best hope of earth.”

He viewed honesty as a primary democratic virtue. Throughout his life, he distrusted political passion and was deeply committed to the use of reason. Arguably his highest political commitment was to the rule of law, which more than any other factor explains his fierce determination to preserve the Union.

Although not a conventionally religious man, he spoke of transcendence more intensely and more beautifully than any other American president, in part because he had experienced great personal suffering, and in part because he believed (with Shakespeare’s Hamlet) that “a divinity shapes our ends, rough hew them how we will.”

What of Lincoln’s habits of mind and intellectual temperament?

In a speech in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1848 he said:

The true rule, in determining to embrace, or reject any thing, is not whether it have any evil in it; but whether it have more of evil, than of good. There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good. Almost every thing, especially of governmental policy, is an inseparable compound of the two; so that our best judgment of the preponderance between them is continually demanded.

Most of Lincoln’s political contemporaries, especially in the 1850s, believed the opposite. They argued that, in fact, most things are either wholly good or wholly evil, and that politics consists of either / or choices between right and wrong, virtue and sin.

In arguing differently, Lincoln reveals a way of civic thinking that he never abandoned, even in dark moments. The idea is that I can find something of value even in views I oppose, just as my opponents, at least on their better days, can find something of value in mine. Lincoln believed that our shared history as Americans – what he called the “mystic chords of memory” – did not necessarily foster this form of civic friendship, but did make it possible.

A related way of thinking which Lincoln also exemplified is the idea that many conflicts are less about good versus bad than good versus good. Saving the Union is good. Freeing the slaves is good. As the nation lurched toward civil war, these two good conflicted with one another. Lincoln’s highest commitment was to the former, but he ultimately struggled for the latter as well, and in the end sacrificed his life for both. He was self-consciously struggling, painfully and imperfectly, with what liberal philosophers a century later would call “goods in conflict.”

Preserving the rule of law is good. Winning the war is good. In 1861, the two conflicted. Lincoln arguably weakened the rule of law that year when he unilaterally suspended the writ of habeas corpus on grounds of military necessity. But he never viewed the choice in binary terms of good versus bad.

Most importantly, Lincoln never saw himself as good and his opponents as bad. Even in war, the harshest of human social struggles, he did not demonize, indulge in abusive stereotypes, falsely exaggerate disagreements, or treat his opponents as less than human or too depraved even to try to understand.

Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America, was Lincoln’s opposite in many ways, including temperament. In 1861 he said: “Our people now look with contemptuous astonishment on those with whom they had been so recently associated.” Lincoln did not think or talk that way. Nor did he respond in kind to personal attacks, even as they rained down on him without cessation. Remarkably, when Lincoln in his Second Inaugural said “malice toward none,” he meant it.

The ideologues around him never really trusted him. Many viewed him as a weakling. Lincoln’s feelings toward them are revealing. He tells his secretary that these radical men are “utterly lawless” and “the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with,” but “after all their faces are set Zionwards.” They’re doctrinal and reckless, Lincoln seems to be saying, but they’re walking toward the promised land of freedom for all. Here we get perhaps our deepest look into Lincoln’s approach to people and conception of politics.

He was fundamentally averse to ideology. This quality in him was seldom praised. He was often noncommittal, seeming to want things both ways. He would bewilder colleagues by telling them, “My policy is to have no policy.” He would change his mind, equivocate, and propose half-measures which tended to displease everyone.

These qualities can seem less than heroic, and they help to explain why many of Lincoln’s contemporaries viewed him as dithering and indecisive. Faced with constant conflict, he was always seeking to soften the edges, reassure and often placate opponents, carve out more room to maneuver, and look for ways to keep the conversation going, no matter how badly it was going.

He had a remarkable ability to work with, and ultimately win the loyalty of, leaders of nearly diametrically opposed views. All his life Lincoln told people that Henry Clay of Kentucky, who was often called “The Great Compromiser,” was his “beau ideal of a statesman.”

As styles of communication, he consistently chose humor over vitriol, understanding over judgement, telling stories over delivering lectures, and making suggestions over giving orders. A strong and confident man, but one who also experienced dark depression, he was mild-mannered. His capacity for empathy was striking to the people around him.

Coda: First Inaugural Address

Nearly the entire First Inaugural was an appeal for the restoration of trust. He speaks directly to southerners, seeking to reassure them that the government will not threaten their peace, property, or personal security. He insists that as president he cannot legally interfere with slavery in the southern states and has no desire to do so even if he could. He reiterates his support of the Fugitive Slave Law. He does refuse, as did most Republicans, to accept the Supreme Court’s pro-slavery Dred Scott decision as final, but even here Lincoln equivocates and avoids strong language. The tone throughout, according to the respected Lincoln scholars J. G. Randall and David Herbert Donald, “struck the note of gentle firmness and breathed the spirit of conciliation and of friendliness to the South.”

Citing law and history, Lincoln argues that the Union is perpetual, cannot consent to its own destruction, and therefore cannot be legally undone on the “mere motion” of one or a group of states. He says that, as a president sworn to uphold the law, he has no legal authority under the Constitution to “fix terms for the separation of the States.” He says that he trusts that this fact “will not be regarded as a menace” and that in carrying out his “simple duty” to defend and maintain the Union “there needs to be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be done unless it is forced upon the national authority.”

Like a lawyer speaking to a jury, he suggests that separation would make the nation’s current problems worse, not better. He appeals to reason: “Physically speaking, we cannot separate.” He proposes that in a democracy the ultimate wisdom of the people can be trusted to prevail and he reminds those who would oppose his Administration that even bad governments have limited powers and limited terms of office. He says that both north and south “profess to be content with the Union, if all constitutional rights can be maintained,” and pledges again that these rights will be maintained. He pleads for calmness. He argues against a rush to action: “Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time.” He closes by appealing to “our bonds of affection” rooted in “the mystic chords of memory.” And finally, he promises that we will be “again touched” by “the better angels of our nature.”

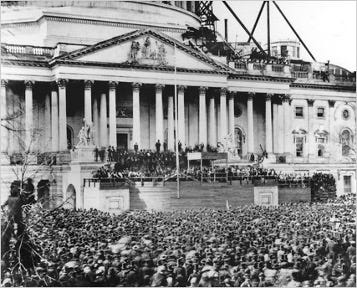

In practical terms, the speech was a failure in nearly every respect. Hardly a southerner attended the inauguration ceremonies. Many southern newspapers, especially in the Deep South, simply ignored Lincoln’s address, and those which did not frequently mangled and misrepresented the text. Southern commentators commonly portrayed Lincoln as an untrustworthy hypocrite, claiming in the speech that he did not want civil war while promising in the same speech to do what would cause one. An editorial in the Midgeville, Georgia, Southern Federal Union said: “Mr. Lincoln talks with a forked tongue.” On Inauguration Day the Richmond Examiner called Lincoln “a beastly figure” whom “no one can hear with patience or look on without disgust.” The next day the Richmond Enquirer said that Lincoln’s address consisted of “the deliberate language of the fanatic.”

Lincoln took office as a beleaguered president, widely disliked and mistrusted in the country. Many in his own party viewed him as a crude, unreliable man. Many in the South viewed him as a would-be despot, while many others in all parts of the country viewed him as a weakling who could be controlled by others. The immediate result of his election was further to divide an already divided nation. His Inaugural Address did little to change any of these realities. Five weeks after the speech, Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and the war came.