Muste’s Way

He wanted to see J. Edgar Hoover about communists.

A. J. Muste was born in the Netherlands in 1885. Six years later his family immigrated to Grand Rapids, Michigan, which had a thriving Dutch community anchored in the Calvinist traditions of the Dutch Reformed Church. When young Abraham Johannes Muste first set foot on U.S. soil at Ellis Island, in the New York Harbor, a hospital attendant who could speak no Dutch affectionately referred to him as “Abraham Lincoln.” The Dutch-speaking child at first thought that “Abraham Lincoln” might be a town, but soon enough he began, as he put it, “to read everything by and about Lincoln that I could lay my hands on,” such that his feeling for Lincoln eventually became “a part of my inmost being.”

In 1909 he was ordained as a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, but ten years later, radicalized by his opposition to the Great War and by his involvement with striking textile workers that year in Lawrence, Massachusetts, Muste left the church and abandoned Christianity. Through the mid-1930s, he was active in labor organizing and in radical politics. In 1936, he re-embraced his Christian faith. Over time Muste’s journey led him to the Society of Friends (the Quakers) and to ministerial posts in Congregational and Presbyterian churches. But Muste’s truest Christian witness, both within the church and in the larger society, expressed itself in struggles for social justice, nonviolence, and peace.

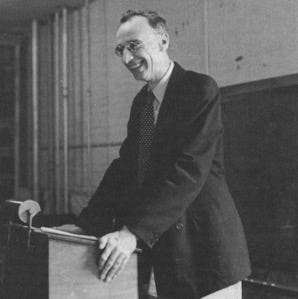

Tall, lean, and frugal, Muste had simple tastes, avoided bank accounts, and admitted to “a strong aversion to money-making.” In Peace Agitator, Nat Hentoff’s biography, Hentoff reports that Muste “gives the impression of owning only one suite.”

Many people who knew him describe him as serene and, astonishingly for a political radical, almost never given to zealotry or self-congratulations. Quiet and soft-spoken, he avoided the limelight and usually did more listening than talking, even when he was in charge. He laughed often, including at himself. He was a Christian mystic who was fiercely intellectual and read constantly.

Partly owing to his study of Mohandas Gandhi, Muste in his work as a peace activist became America’s foremost early 20th century exemplar of the philosophy and tactics of nonviolent resistance. In 1949, a young student at Crozier Theological Seminary, Martin Luther King, Jr., was first exposed to these ideas when he heard Muste give a lecture on the topic. The two men became collaborators. Years later, at the height of the sit-ins and other nonviolent protests of the U.S. civil rights movement, Dr. King said: “I would say unequivocally that the current emphasis on nonviolent direct action in the race relations field is due more to A.J. than to anyone else in the country.”

For most of five decades he was a leader of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a nondenominational pacifist organization committed to nonviolence and international understanding. In this work, Muste had great empathy and listened to everyone. He did not end relationships.

Starting in about 1955, Muste, a strong anti-communist, initiated a series of private conversations with American communists who were considering leaving the party. One of those who met with Muste during this period later said:

We had been trained to believe that there couldn’t be anything decent or honest in ‘liberals’ who weren’t in the party, but it was revealing to recognize the thread of principle that ran through everything a man such as Muste did and said. Most of the other non-Communists were thoroughly suspicious of those of us who were having doubts … I say this as an atheist, but if I were to be asked if I’ve ever known a saint, I’d have to say Muste comes close.

As a result of these and similar efforts, Muste was publicly accused of disloyalty by the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, who in 1957 reported to a U.S. Senate investigating committee that Muste “has long fronted for Communists.” Muste wrote a long letter of reply to Hoover, detailing his long-standing opposition to communism as well as his on-going conversations with party members. He closed by saying that, while “conscientiously opposed to responding to summons to appear before any government official or agency engaged in investigating the political or religious opinions of myself or others,” he [Muste] would “appreciate it” if Mr. Hoover “should have time to discuss these matters with me on a personal basis.” Director Hoover did not respond.

Asked about his approach, Muste said:

One has to be both a resister and a reconciler … You have to be sure that when you’re reconciling, you’re also resisting any tendency to gloss things over; and when you’re primarily resisting you have to be careful not to hate, not to win victories over human beings. You want to change people, but you don’t want to defeat them.

Part of Muste’s genius in bringing people together is that he never succumbed to the belief that he spoke truth and that his opponents spoke error. He said:

You always assume there is some element of truth in the position of the other person, and you respect your opponent for hanging on to an idea as long as he believes it to be true. On the other hand, you must try very hard to see what truth actually does exist in his idea, and seize on it to make him realize what you consider to be a larger truth.

This was Muste’s civic way.