Wilbur’s Idea

He had to see a man about a pig.

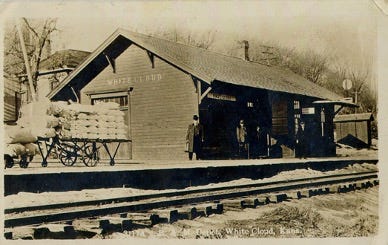

It’s 1913 in White Cloud, Kansas, a small town in the far northeastern corner of the state on the Missouri River. Our civic story concerns a ten-year-old boy named Wilbur, who had to see a man about a pig.

Wilbur’s parents, Charles and Manie Chapman, were Christian missionaries. Both had attended the University of Kansas and together had found their life’s calling as part of a YMCA-inspired youth religious revival which had swept across Kansas in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Inspired by faith, the couple dedicated their lives to an organization called the World’s Gospel Union, later the Gospel Missionary Union, devoted to global Christian evangelization.

In April of 1913, Wilbur’s father, Charles, was home on leave, having spent more than a decade abroad selling bibles and preaching the gospel in Ecuador and Columbia. His mother Manie, whose health had become too poor to remain overseas, was supporting the Union’s work from their home in White Cloud.

Responding to the biblical injunction to “cleanse the leper,” Mrs. Chapman started prayer groups in the area to seek God’s help in caring for the world’s lepers. When she thought the time was right, she wrote to the head the American Mission to Lepers, a man from Boston named William Danner. Come visit us in White Cloud, Mrs. Chapman wrote. We’re praying for the lepers. If you’ll visit our churches, she said, I believe you can raise $250, enough to care for ten lepers for a year.

A good and dedicated man – like Wilbur’s parents, he had come out of the western YMCA movement and as part of that work in 1903 had started a YMCA “health farm” near Denver, Colorado, for boys suffering from tuberculosis – Mr. Danner went to White Cloud. He stayed in the Chapman home. He befriended young Wilbur, who soon enough was calling him “Uncle Will.” He visited and spoke in four local churches – in a town of about 750 people – and raised a total of $225 for the American Mission to Lepers. Mrs. Chapman apologized to him for not meeting their goal of $250.

At the train station before dawn, waiting to head back East, Danner recalls that he took three silver dollars out of his pocket and “slipped them into Wilbur’s hands as I said good-bye, asking him not to show these to anyone till morning.”

Several weeks later Danner got a letter from Wilbur. In the fall, Wilbur wrote, I’ll use the three dollars to “buy a pig, and feed him, and see if he will not grow big so I can sell him for enough to support a leper for a year … Mother’s tenth leper! Do you see?”

Danner saw. In November he got a second letter. Wilbur had bought the pig. Moreover, the pig was becoming a local celebrity. Neighbors had learned about Wilbur’s idea, and children in town were eager to help feed “the leper pig.” The pig was growing rapidly. Wilbur had named him Pete.

In the spring of 1914, Wilbur sold the pig and sent $25 to Mr. Danner, finally raising the town’s contribution to $250 and thus completing the pledge for “Mother’s tenth leper.”

That’s how the story begins. Moved by what Wilbur had done, Danner shared the story with friends at a prayer meeting. One of those friends worked at the Sunday School Times, a national publication for Sunday School teachers. He asked Danner to write a story for the Times about Wilbur and the pig. Danner agreed.

The story caught on. Sunday School teachers across the country began collection drives in which children would contribute coins to “feed Pete” to help the lepers. Soon the American Mission to Lepers was distributing thousands of metal (later, plastic) “Pete the Pig” banks for children to fill with coins. By 1919, 11,000 “Pete the Pig” banks had been distributed to U.S. Sunday Schools. By 1938, the number had reached 100,000, and contributions to the American Mission to Lepers from Sunday School children had exceeded $1 million.

When you were a child, perhaps you had a “piggy bank.” Do you wonder who conceived this idea and what made these little banks so popular? There’s no single answer. Linking the concept of pigs with the need to save money has been around for centuries. For example, earthenware money-boxes called “penny pigs” or “pinner pigs” were popular among British children in the 19th century. But one apparently important influence on the evolution and popularity of the “piggy bank” in the U.S. was the success of the “Pete Pig” campaign, which grew out of Wilbur’s civic idea.